Practical Guide to Music Theory and Improvisation

This is a dump of everything I know about music theory and how I apply it to play music with other people. If you want to learn just enough music theory to start improvizing and making some basic compositions for yourself, this might be a good guide for you.

Or, if you're already proficient with your instrument, but you'd like to find out how the theory behind it works, this should cover most of the basics without going too deeply into it.

Still, this guide will be really dense with information and it's not realistic to expect to get it all from skimming it once, but I'm still hoping to show that progressing to improvisation and writing your own stuff might not be that drastic of a jump. To do that, as a disclaimer, I'm gonna simplify or completely omit a lot of things that I don't think are important for a beginner. I'll also try to be generic, but some of the practical tips and tricks might unavoidably end up guitar-specific, just because that's what I'm most familiar with.

Why Do This

I started playing guitar some 10 years ago, but I didn't particularly want to play an instrument that much. I mainly wanted to compose my own music, and guitar was just a tool to learn the composition skills - how are riffs and melodies actually constructed? What makes this part of the song sound good? What makes it bad? Those questions are what drove me to spend more time reading about the theory instead of actually playing the instrument.

And for a non-professional player next door, I found out you really don't need that much of it. The bare basics will be enough to jam with friends, improvize your own riffs and solos, and turn some of that into full songs. Right now, I don't feel like learning anything beyond this would make me a better musician - I don't feel bottlenecked with the lack of understanding of music theory anymore, but rather by a lack of imagination and physical dexterity with an instrument, which are two completely different problems.

But the point is - I think you should learn those things, they will unlock you some cool new abilities. And after you feel comfortable with the basics, you can rest, as there's a huge chasm until the next levels of musical understanding, which hopefully neither you and I would have to cross unless we decide to become classical composers or something.

Notes

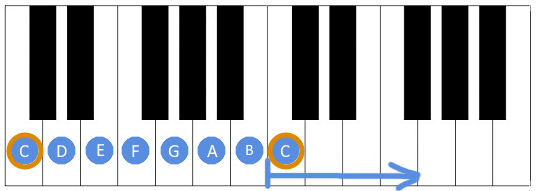

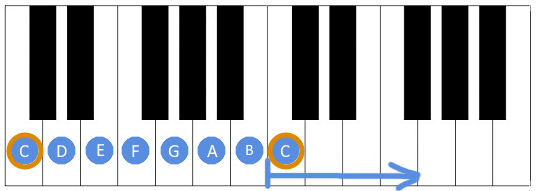

First, we have a note. In modern western music, you have 7 of them: C, D, E, F, G, A, B, and they repeat across the board. Let's show it how it looks on a piano:

We start with C and go through the notes one by one, and after the last one, we start with C again and then repeat the whole thing throughout all the other keys on the piano.

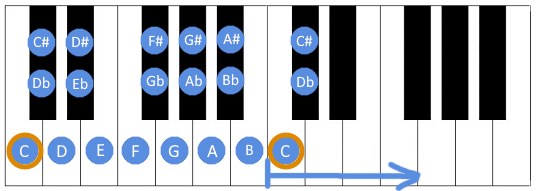

Each note can be sharp or flat. This means that it's either raised or lowered in pitch by half a step, so it's like in the middle of two notes. You can see that on a piano, those are the "black keys":

If we "raise" a note G, it becomes G sharp, which we write as G#. If we "lower" it, it becomes G flat, or Gb. You can see that, for example, C# and Db are played by pressing the same key on a piano. The name of that note varies based on the context in which you're using it, but for all practical purposes they are the same note and you can use whichever name you want.

One more tidbit - in German-influenced countries a note B is written as an H. Don't get confused, it's the exact same note.

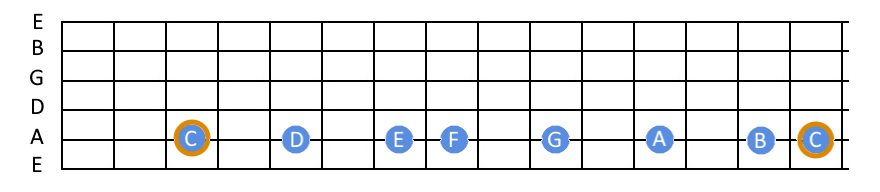

On a guitar, the notes are laid out differently:

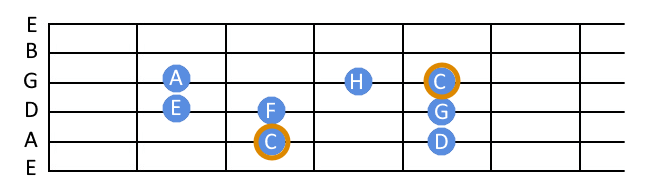

Although in practice, as guitar has six strings and notes repeat across them, a more conventional way (albeit a bit confusing at this point) of showing them would be like this:

You can see there are no specially marked "black keys" here - but the sharp and flat notes still exist between the regular ones. Same thing as on a piano.

Notes on a guitar might seem more confusing at first, but it's the more natural way of how the notes work, because when you look at the underlying physics behind it, there's no real-world difference between a "white" or a "black" note. That's just a convention we invented to make the following simpler: the scales.

Scales

Scales are ordered sets of notes. In most practical usages, a scale consists of 7 notes, and can be either major (happy-sounding) or minor (sad-sounding).

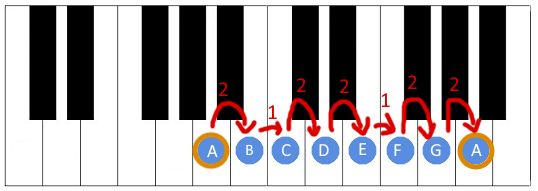

As an example of a scale, here's what the C major scale looks like on a piano:

Yes, you can see here that it's the same picture as above - pianos are made so the C major scale is the "default" one. If you just play those 7 white keys in order, you will have played a C major scale.

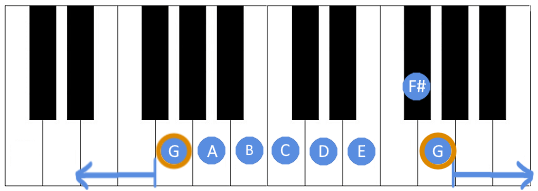

But for a different example, let's take a look at the G major scale. Its name means that instead of C, we're starting our scale at G instead. But apart from that, it also uses one black key, where instead of F we're using F#:

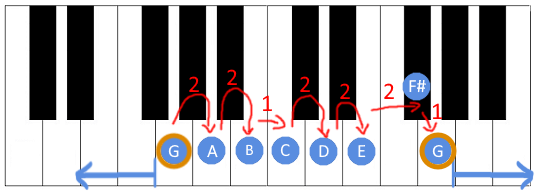

How to know which scales are made of which keys? There's a formula for that, and for major scales it's 2 2 1 2 2 2 1. This means, for example in G major, that we will start at a note G (what we call a "root note"), count notes by the formula, and each note we step on will be contained in that scale. As shown here:

At the end of the formula, you're gonna reach the same note that you started from, which we call an octave.

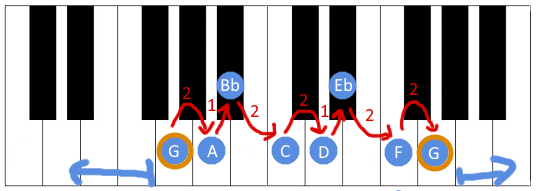

For minor scales, which sound sadder, the formula is a bit different: 2 1 2 2 1 2 2. Let's apply to G, and construct a G minor scale.

This scale differs quite a bit when compared with G major scale, which is why it also sounds different.

It also contains two flat notes. But why did we name one of them Bb and not A# if they're the same note? Just for convenience. We already have a note A in this scale, so we don't want A# in it as well - if you were to write this as sheet music, you'd prefer to keep each note in its own row there. But in most practical purposes, it's a rose-by-any-other-name situation, exact same note, regardless of how you name it.

If you try to apply the same formula to construct the A minor scale, you're gonna notice something interesting. It also uses white keys exclusively, just like C major does!

Even though it's using a different formula than C major. The thing is - for each major scale, there's a companion minor scale that uses the same notes, and vice-versa. The only difference between them is that they start and end on a different note, the note that names them. Such two scales are said to be relative, if anyone asks.

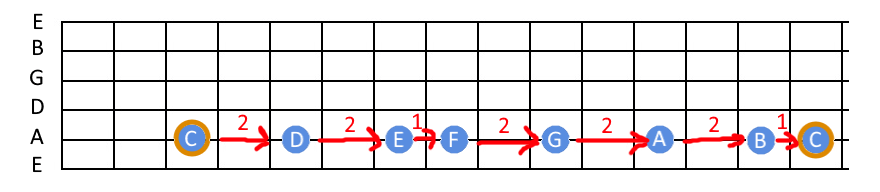

Let's see how to build a major scale on a guitar. The formulas remain the same, and in fact, they're even easier to count due to the lack of black/white keys distinction:

I don't know how piano players learn this - but on guitar it's pretty easy to just learn the patterns and shapes of scales, and never think about the formulas. Once you learn a shape for one major scale, you can play any other by just moving the shape to a different note. You can't do that on a piano due to the somewhat artificial black/white keys distinction.

So what do we do with scales? We are going to base our melodies on them eventually, but for now we're just gonna use them for practice. Try playing the scale as it is, note by note. You start from the root note, then play each note in ascending order until you reach the root note an octave higher. Then you play it backwards until you get to where you started from. Repeat for some time until you get bored. The idea is to get familiar with this framework so you can write your melodies inside of it.

I would suggest you just pick one scale, any scale, learn what and where the notes are, and just stick with it until you know it by heart. It will be a good enough solution for the start, and the formula will get engrained in your fingers through the patterns. Later you can use that knowledge to construct any other scale you will need.

Keys

We said that scales are what we're basing our melodies on. When you write a few riffs using A minor scale and pack them in a song, we say: "that song is in a key of A minor".

A key and a scale are similar things - both are using the same notes, with the difference that in scale you're always playing them in order, whereas in a key you don't have to. It's a bit confusing as they're related but different concepts.

When you set out to write a song, you will first need to choose which key you're gonna write it in, as it determines which notes you can use. Even when just improvising, you need to agree with your bandmates on those things. So you're probably gonna say something like "Hey guys, let's play this one in the key of A major". This means you'll restrict yourselves to only use the notes from that key/scale, otherwise things might sound really bad.

So what do we do with this? For now, we just have to remember a shorthand - everything we play, be it an existing song from someone, or an improvisational jamming session, it should be in some key, only use the notes present in it, and avoid the ones which are not.

If you were to include all the possible notes in a single song, including the sharp and flat ones, the number of potential note combinations goes through the roof, and some of them sound really sour. For now, you can avoid that by just sticking to notes from a key. When you get more experience, you're gonna realize that this is not really a strict rule, but until then, just stick with some key, doesn't matter which one.

To test this out - pick a key, let's say A minor, and search for something like "A minor backing track" on Youtube. This will give you an instrumental in that key, and you should be able to play your scale over it. Try it - it might not sound great, but it won't sound bad like if you played random notes, so it's a step forward.

Intervals

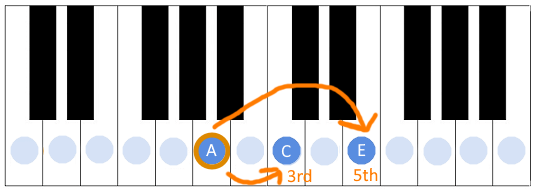

We use intervals to express the distance between two notes in a scale.

For example, in C major scale, notes C and D are one step apart, so we say that D is a second of C. Note E would be a third of a C, and so on. There's fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, and for eight we just call it an octave. As we're working with 7-note scales, the octave will be the same note you started from.

There are more intervals and variations to them, but let's stick to this for now.

Chords

When you play multiple notes at the same time, you get a chord.

In modern western music, which this article is concerned about, a chord means playing three or more notes at the same time. But you can't play any three notes - there are (again) formulas you could use to figure out which combinations would or wouldn't work.

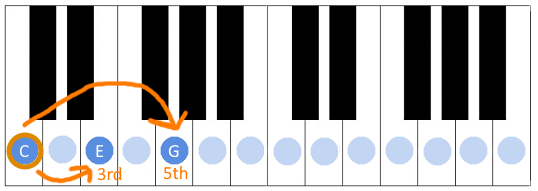

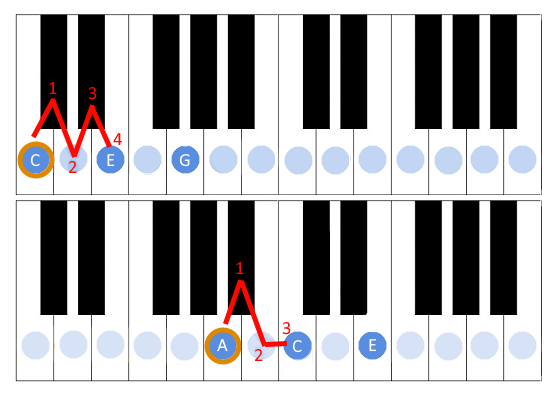

We construct a chord by stacking intervals. We take some note, add its third interval, then its fifth. This is a chord. Here's an example of how you would make the C major chord, inside of a C major scale.

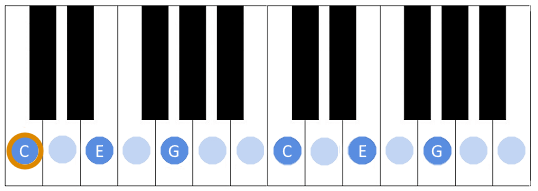

Like with scales, those notes can repeat in a single chord. This will also be a proper C chord:

In fact, if you play a G chord on a guitar and try to see which notes it's constructed from, you're gonna see that it contains a fair share of duplicate notes - G B D G B G. So it's three Gs, two Bs and one D. This is okay.

Also like scales, chords can be major (happy) or minor (sad), depending on which notes they're made from. The G chord above is a major chord, which you can tell by its sound. By convention, if we omit the suffix and just say G, it's implied to be a G major chord.

If you try to construct A chord in the same scale, you will see that it sounds sadder, even though we used the same formula. It's because that one is actually a minor chord. So what's the difference between the two, as we're using the same first-third-fifth formula to construct both?

The thing is that their third intervals are not the same. If you count the number of steps from first step to third one (including black keys), you can see that the A minor chord's third interval has a difference of three steps (actually called half-steps or semitones), while the C major one has four:

That's a small detail we didn't mention while talking about intervals - that they can also be major or minor. Even though they are both a third interval because they are referring to the third step of the scale, we call them a minor or major third interval based on if they're three or four semitones apart. And this is what causes the difference in their sound.

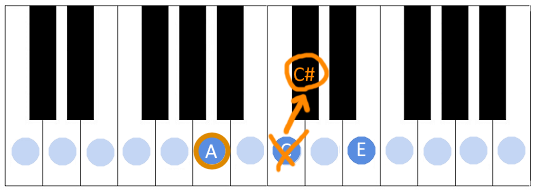

So, for any minor chord, the formula is really: root, minor third, fifth; and for major ones it's root, major third, fifth. In practice you don't need to think about this much, but I think it helps in understanding all of this.

With it, we can convert any minor chord to a major chord just by raising its third interval by one semitone, and vice-versa if we lower it. For example, we can convert A minor to A major by replacing C with C#:

While we technically can do this, we have to be careful in which key are we - it the context of a current key of C major, which doesn't contain the note C#, it wouldn't be a good idea to use either that note or any of the chords containing it! This was the purpose of being in a single key - to reduce the number of possible note combinations and prevent us from making potentially catastrophic harmonic choices, like using C and C# in a same song.

Of course, if you're an expert, you might get away with it, but for us beginners it's better to stick to the ropes until we're familiar with them, and only break the rules after it.

Ok, so how do we know which chords we can use in a particular key?

Chords in a Scale

There are 7 distinct notes in a key, so the number of theoretical chord combinations there is huge. But luckily, as we've seen, not all notes sound good with each other, so in practice we only get 7 chords per scale - one per note.

As each key has 7 notes, and with that 7 distinct chords, three of them will be major, three minor, and the last one a weird one that you can ignore for now.

There's a convention of using roman numerals when talking about chords in context of a key. They are as follows: I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII - each number represents a chord at that step of a scale.

To find out which chords exist in a key, and if they're major or minor, you can use the following shorthand - in major/minor scale, I, IV and V chords will be its matching major/minor chords. For example, in any minor scale, I, IV and V chords will also be minor chords. In any major scale, those same steps will contain the major chords.

All the other steps of that scale will contain the "opposite" chords, like minor ones in major scale, or major ones in minor. With the exception of that broken one.

So for an example, let's take a familiar A minor scale. The first, fourth and fifth steps will be A, D and E, so we know those chords would be the minor ones. We're left with second, third, sixth and seventh. This is where we have to memorize that second (B) is the odd one that we don't play (because we can't construct a proper fifth for it, feel free to try it), so the rest of them then have to be major chords - third is C, sixth is F and seventh is G.

We said before that relative scales, like A minor and C major, have the same notes. This means they will have the exact same chords as well. So if you try to apply the I-IV-V formula to C major scale, you're gonna see that major chords are C, F and G, which is the same as in A minor scale. The odd B note is now step VII, but we still have the same problems with it so we don't use it, and the minor chords are to be found at steps II, III and VI, which are D, E and A, again, just like in its relative minor scale.

One more thing about roman numeral thingy - usually, if a chord is minor, we mark it as lowercased. So for example, in a minor scale, we would notate it like this: i, ii, III, iv, v, VI, VII.

Chord Progressions

Chords are used to make chord progressions, which is simply the order they are used in throughout the song.

The thing is - each chord in a scale serves some function inside of it. For example, the I chord is a root chord that serves as a tonal center of a scale, which means it's a good way to start a song, to establish the harmonic content that will follow.

Since it's a tonal center, it's also a great way to end a song. For a song in A minor scale, ending on its namesake A minor chord would provide the most satisfying resolve at the end of a musical phrase.

To resolve the song (or a single phrase) effectively you need to create some tension first, which you can do by using some other chords, like IV or V. So let's say you start with I, alternate between IV and V to build it up, and then drive it back home to I. This is one of the most commonly used chord progressions in modern western music, just called I-IV-V.

If you sneak some minor chord in there you'll get an even more popular I-V-vi-IV progression, basically a blueprint progression for the majority of popular music you're listening to.

Chord changes are a game of switching between stability and instability throughout the song. It's a hero's journey - you start with some stable chords, introduce some tension, then you resolve it back home.

As far as I know, there's no canonical list of each chord's "purposes" in a scale, but you'll see that each of them works differently in a context of a scale.

Try it yourself - with an instrument of your choosing, pick a scale, find which chords are in it and play some progressions to see how they work. There's really only finite amount of combinations, especially if you're only working with those base chords that we mentioned so far.

Some things in music are hard to figure out (like chord identification, I can't recognize if I'm hearing a II or III chord, it all sounds the same to me), but the tension/resolution thing is pretty straightforward that you can feel by just playing the few chords on your own.

If you want to make something sound good (or just not bad), for starters you can stick to I-IV-V or I-V-vi-IV progression, maybe sprinkle some other chords inside of it. As you get better with this, you learn where you can break the rules - it's not impossible or forbidden to end the song on a V, but you really need to know what you're doing to be able to pull it off.

Anatomy of a Melody

Chords and their progressions are the harmonical foundations of a song. They're fine, but what really makes the song is some melodic content over it.

Melody is a sequence of notes, so it's almost like playing a scale, but with note and rhythm variations thrown in. Melodies can be interesting on their own, but when they are played over a chord progression, they get stronger because the notes from the underlying chords provide additional harmonical content to them. And the opposite is also true, a note in a melody can make a certain chord change happen more smoothly.

Unfortunately, this is where things get fuzzy and rules stop existing, so we can't talk in absolute truths. The only thing we have are shorthands, and even they might be cultural and not something universally applicable. But let's try it anyway.

One "rule" of what makes a melody is skips and steps, which says that the melody should sometimes move through neighboring notes in steps like a scale does, in some general but not exclusive direction, but also make a few bigger skips here and there to surprise the listener (after all, no one wants to listen to you just play a scale). So let's give a few examples.

If you wanted to write a nice and happy melody, you would pick a major scale, start the melody with a root note, play more nearby notes in some general direction upwards or downwards, make a few unexpected jumps, and then land back home at the root note.

If you wanted something more somber, you could pick a minor key, start it the same way but make it slower and go in descending direction. You might not even resolve it back to root note and leave the listener hanging.

If you wanted to make a melody that sounds stressful and confusing, you could skip erratically between notes or alternate between fast and slow parts.

Whatever you do, one thing that is important here is that you need to make the melody play well with the underlying chords. For example, if you're currently playing a A minor chord, which contains of notes A, C and E, a melody containing those notes would sound okay over it. It's a safe option which won't sound bad, but it might be boring, as you're just regurgitating the notes that the chords are already playing. You might need to sprinkle other notes in there to make it more interesting. But you're quickly gonna notice that some notes might not work well. Playing a G note over A minor chord would sound okay, but F will be too dissonant. This might work fine in jazz, but it won't fly if you're writing a pop song.

The interplay of melodies and underlying chords is something that falls under the domain of harmony, which can get complicated and would require us to stop simplifying things, so let's leave that for some other time.

Regarding melodies, it all depends on what you want to do with it, and unlike with chords, the combinations here are truly endless. Here's a list of things you can think about when writing a melody:

There may be more of these "tricks" in the wild, but when it comes to it, writing a melody is a uniquely human thing mostly done by feel, a process that can't be condensed into 10 Simple Steps, which is why even in this highly advanced techno society, Dua Lipa's songs are still not written by AI.

It's useful to notice the patterns and practice them, but when it comes the time to write that damn melody, it might be best to do it by feel. As they say: "practice analytically, perform intuitively".

How To Improvise

Improvisation is nothing more than making melodies on the fly.

All the things from above apply here as well. Melodies will be based on scales, utilizing skips and steps, with variation in notes' rhythm and loudness.

However, in this context, the definition of melody can get pretty liberal, as you probably don't want every single part of a session to be melodic. For example, during the solo, you're gonna want to have some parts which are not as melodic, or are maybe strictly rhythmic or textural, just to make the main melodic segments seem even more melodic in contrast.

Making melodies is definitely a big part of improvisation, but you might need to have other tools in your arsenal to provide enough variance to keep yourself and other people engaged.

If you're soloing over some chord progression, you might think you need to keep track of which chords are being played at which time, to know which notes to play. I personally don't feel like I have enough mental firepower to keep track of all of that and improvize over it at the same time, so I'm mostly basing it on feel. I just check out which key it's in and then base my stuff off of it. It doesn't always sound great, but at worst it sounds only boring and uninspirative, which is ok in my book.

There are a few tricks that I learned which have served me well, so let me share.

If you make a mistake, don't stop playing. No one cares, just keep going. This trains you to become more adaptable to the situation, which is useful even if playing existing songs from other people.

If you make a specific mistake of hitting a wrong note during improvisation and it sounds really bad, what you can do, counter-intuitively, is to play it again. This would make it seem intentional, like you knew what you were doing the first time. It might sound jazzy, where it's not uncommon to include notes from out of key. And in some cases you might even luck out and hit a wrong note which foreshadows the chord to come and maybe even provides a nice transition into it. In the flow of a moment, it seems better to repeat the mistake than to acknowledge it.

Utilize pauses and don't feel pressured to spam notes all the time - sometimes the things you don't play matter more than the things you do.

Listen to other people - leave them some space sometimes, but also sometimes try to sneak a note between two notes they're playing. Harmonize by playing the exact same melody, only by a third or fifth apart, or try playing in a call-and-response format.

The End, For Now

This post definitely grew bigger than I expected. If anything here is incorrect (which is highly possible) or is missing something important, I'd be glad to hear about it, as there's always more to learn about all this.

Some things in this post are a bit simplified, as I didn't want to go any deeper than I had to, so there's definitely more stuff to write about in some part two of all of this someday.